Katie Tomlinson: Fight the Moon - a review of the exhibition at Paradise Works, written for Corridor8 in December 2021

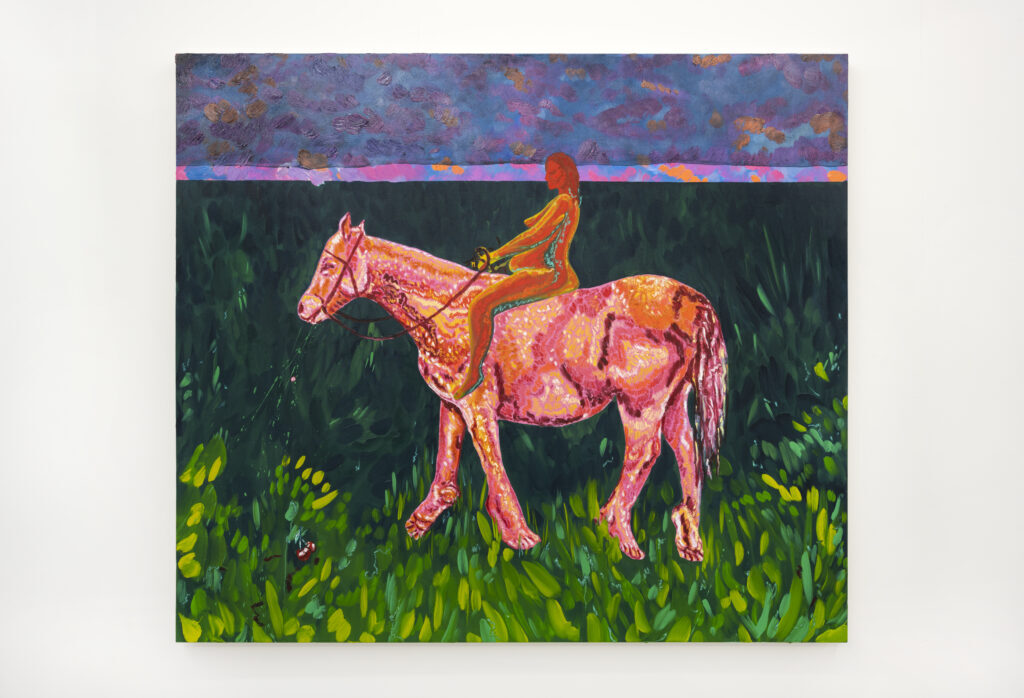

The first thing I notice is colour. The paintings awash with fluorescent pinks, deep crimsons, and luminous blues. I’m surrounded by canvasses that glow – each demanding attention – and it’s almost overwhelming. After a few minutes that arresting intensity begins to dissolve, and each painting, in turn, exposes its true self. Katie later clarifies that this is quite deliberate, she plays with over-stimulation as a means to seduce and entice. It certainly works. I find myself stood before a rotund fuchsia dappled horse, its tail droops, its mouth drools. Then, on closer inspection, I realise its hooves are replaced with impossibly arranged human feet. They appear to flop and drag awkwardly over depleted fauna; just two large red cherries suggestibly remain. In another painting a girl with pink-bowed pigtails holds aloft the severed head of a St Bernard. Maybe an absurd take on Caravaggio, I think to myself, like his painting of David brandishing the head of Goliath. The girl’s nose runs, her tutu is blood splattered, and decapitation considered, the dog’s expression somehow remains noble. It’s all quite menacing and unnerving.

Katie is an artist who clearly enjoys the darkest edges of comedy, but also unashamedly embraces silliness. When we chat, she surprisingly cites Joe Lycett’s recent toe-dip into art, but once explained, it makes complete sense. Humorous surfaces are a means to draw you in, to stealthily proffer debates around society and politics. Indeed, it becomes evident that most of Katie’s artistic influences do just that. Lindsey Mendick, Daniel Richter, Lubaina Himid, and Martin Kippenberger are referred to, but it’s her mention of Beryl Cook that I find most interesting. Cook’s work has been long relegated to greetings cards and jigsaws, but it’s easy to forget that she often dealt with uncomfortable issues like class, homelessness, and sex work. Cook laboured against the delusion that you can’t be both a womxn * and a painter. Katie explains how she also grew-up with this invalidating perception looming over. Her approach, though, is not to deny male artistic influences, but to select elements of their work, and make these pertinent to femxle experience. Katie’s paintings are, after all, full of male art-historical nods, whether that’s the claustrophobia of Francis Bacon, the grotesque bodies of James Ensor, or the brazen flippancy of Werner Büttner.

This is an exhibition about womxn, with paintings exploring patriarchy, sexual desire, disaffection, alienation, and the male gaze. They often relate to personal experiences, and therefore the idea for the image comes first. Katie begins by scouring websites, magazines, and books to find reference material that matches her mind’s eye. She then makes a collage to define the composition, before tracing its outline in black ink. Then a separate sketch is made for colour arrangement. Although mostly predetermined, the final paintings, I am told, are often a surprise, with hidden meanings or buried experiences becoming unearthed during the application of paint. Take for example another work; a series of figures are seen sitting around a large maroon table, their faces liquefying into each other, and two dogs are seen tussling in a carnal embrace underneath. Katie explains that the objects on the table, such as an ashtray, a bottle of Gaviscon, three-tier-cakes, and chicken drumsticks, came as unexpected. We can all relate to these as symbols, but some of their complex meanings will remain just for her. Of all on display, this is surely the most personal work. There’s a self-portrait of Katie at the centre, holding an extravagant bouquet of roses, seemingly unwavered by the discord surrounding her. She explains that painting can often be a lonely and introspective exertion, and Katie presents herself here as separate, secluded amongst her surreal companions.

This inaugural exhibition is the first time Katie has worked, in any serious way, with a curator. She explains that developing the show with Zoe Watson (Curator, Holden Gallery) was an illuminative experience, facilitating new ways to consider her own work. Initially, the plan was an early career retrospective (of sorts) including sculptural work and ceramics, but the decision to focus on Katie’s painting alone is ingenious. Each canvas, simply presented, allows for a fundamental understanding and alluring introduction to her practice. As I walk around the exhibition, and examine the paintings more closely, I also soon realise that Katie is an artist in love with paint and what it can achieve. There’s a noticeable speed and confidence to the brushstrokes. Thick furrows of oil that advance towards skin highlights assuredly picked out in white and peach, rumpled fabric blocked-out in teals and leafy greens, or the long channels of tree trunks delineated in mauves, carving a pictorial plane. One of the smaller works catches my eye with its deliciously painted sushi, but on second glance I realise they sit atop a naked femxle torso. I’m jolted by a scene of objectification, and once again Katie compounds my judgements; this is mature and perceptive painting.

Fight the Moon is a dazzling presentation of Katie’s work; intense, exaggerated, loaded with vaudeville camp, but at the same time murky and disquieting. The exhibition is an energetic journey that offers access to an uncanny and captivating world, an entrancingly curated showcase for a talented artist.

* ’Femxle’ and ‘womxn’ are both used, at the request of the artist, as inclusive and intersectional ways to define gender with no relation to patriarchal norms.

Image: 'when she came back she was nobody's wife' (2021). Image courtesy the artist and Paradise Works.